30 January 2020

Climb in, take off and fly away over the stationary traffic below: This fantasy from the realms of science fiction may well become reality in the coming years. All over the world, young start-ups, but also some of the venerable giants of air travel, as well as carmakers, are working on ways to move passengers from A to B in the air above the city streets or from one city to another.

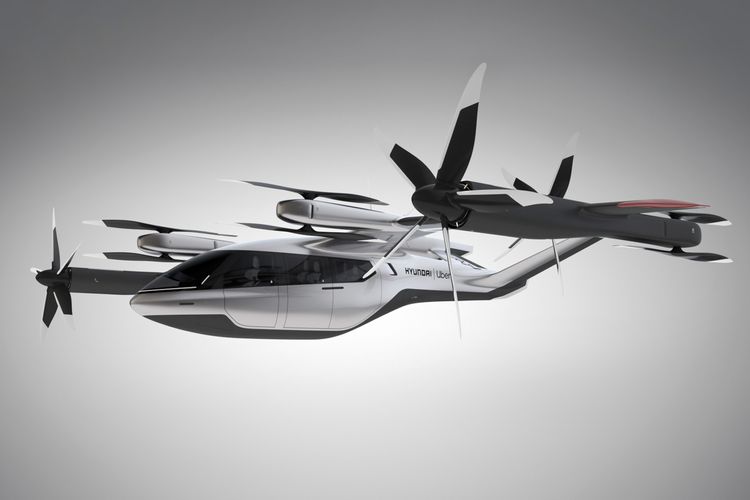

Video recorders, CD players, DVDs or the Commodore 64: the list of electronic innovations that first saw the light of day at the Consumer Electronics Show in Las Vegas is a long one. In the meantime, more and more car manufacturers are using what is arguably the world's most important consumer electronics trade fair to present their vision of the mobility of tomorrow. They’re showcasing self-driving cars and electric vehicles and even taking the aerial route: This year, Korean automaker Hyundai and ride-hailing company Uber unveiled a flying taxi model in Las Vegas with which they are hoping to take over urban airspace for mobility services. Known as S-A1, it’s what is referred to in short as an eVTOL (electric Vertical Take-Off and Landing) aircraft. Designed for a cruising speed of up to 290 kilometres per hour, this aircraft, which has been designed to carry four passengers, is intended to travel up to 100 kilometres on a single battery charge and to be capable of being fully charged at peak times in just five to seven minutes. Uber plans to launch the craft for commercial flights as early as 2023 – offering a cheaper and quieter alternative to the helicopter flights that the company has since October 2019 been offering wealthy New York customers to ferry them from Lower Manhattan to JFK International Airport during the rush hour for around 200 dollars per head.

© Sarah AbboundHyundai and Uber joined forces in the development of a flying taxi model.

Over 75 air taxi projects worldwide

Uber is far from the only company that is seeking to realise the dream of airborne urban traffic in the coming years. Management consultancy Roland Berger counted 75 flight taxi projects in a study at the end of 2018.

Airbus, for instance, sent its first ever electric air taxi skyward in May 2019. The CityAirbus successfully took off and landed without human intervention on the company premises in Donauwörth, Bavaria. Although it has to be said that no altitude records were broken in the process. For safety reasons, the electric helicopter equipped with four double rotors was anchored to the ground with steel cables attached to its skids, meaning that it was only able to ascend a few centimetres. It was only at the beginning of 2020 that the demonstrator was allowed to fly without a safety cable for the first time – staying aloft for five minutes at a height of two metres above the ground. An extensive test programme is scheduled to start this year at Manching airfield near Ingolstadt.

Ingolstadt is one of the model regions for testing drones and flying taxi concepts within the framework of the EU's Urban Air Mobility initiative. German politicians have also signalled their interest in aerial mobility options. At the first presentation of the CityAirbus, Federal Transport Minister Andreas Scheuer pushed for the rapid creation of the legal framework needed for the deployment of the new aircraft. “We don’t have to wait for the engineers to get these aircraft fully ready to fly before enacting the legislation they need to fly them,” the CSU politician said. Airbus engineers are now working in Manching to develop a prototype that will match the planned production model in most respects. In the future, the latter will transport four passengers for up to 50 kilometres on fixed routes in major cities at a top speed of 120 km/h – initially with a pilot behind the controls, but later autonomously.

Airbus’s American competitor Boeing launched its prototype air taxi with eight propellers and four wings into the air in January 2019. At Manassas in the US state of Virginia, the aircraft successfully took off, hovered and landed again. The 9-metre long and 8.5-metre wide vertical take-off aircraft with its target range of 80 kilometres was developed by Boeing subsidiary Aurora Flight Sciences. It only took one year to get from the conceptual design to the flying prototype, Boeing says. But it’s likely to take a lot longer to get to the point of series production. First of all, the aircraft needs to be able to handle the transition from vertical take-off to forward flight. This is considered the biggest challenge in the development of a vertical-take-off-and-landing aircraft.

Electric planes from Munich

German start-up Lilium has already successfully overcome this hurdle. After its maiden flight in mid-2019, the Munich-based inventors’ e-jet of the same name didn’t just complete some complex manoeuvres at a speed of more than 100 km/h, but also managed the transition from vertical to horizontal flight.

The aircraft is powered by 36 electric motors and, as with Boeing, has four fixed wings. These wings make the e-jet is significantly more efficient than rotor-driven aircraft, and, with a range of 300 kilometres, the start-up is confident that it will be able to travel much further than most of its competitors. The lift generated by the two pairs of wings means that the jet needs less than ten percent of its maximum power output of 2,000 hp in horizontal flight and uses about as much energy as an electric car over the same distance.

“We don’t have to wait for the engineers to get these aircraft fully ready to fly before enacting the legislation they need to fly them.”

By 2025, Lilium intends to be operating in various cities around the world, flying five passengers per flight to their destinations. The first production plant in Weßling near Munich is already complete, and a second factory is planned at the same site. Lilium plans to produce hundreds of aircraft per year here until such time as it can commence commercial operations. First, however, the start-up needs to make step-by-step improvements to the technology used in its air taxi. According to media reports, Lilium has repeatedly been confronted with engine failures and other faults. As a result, the unmanned prototype has so far been flown by remote control.

Manned flight over Singapore

Its competitor, Volocopter, is already a few steps ahead. This company from Bruchsal near Karlsruhe has been working on its flying drone for two passengers since 2011. 18 rotors and multiple redundancy in all flight-critical systems should make the aircraft as safe as it can conceivably be.

After test flights in Dubai, Finland, Germany and the US, the Baden-based start-up completed its first manned flight over a major city, Singapore, in October 2019. Equipped with 18 rotors, the air taxi flew over the port district of the Asian metropolis for two minutes and 30 seconds. One month earlier, the unmanned Volocopter had for the first time taken to the air over a major German city. The city in question was Stuttgart, home to the headquarters of the Daimler Group, which has had a stake in the company since 2017. “I’m convinced that we’ll be able to solve urban congestion problem on specific routes,” said Daimler CEO Ola Källenius before the test flight, succinctly describing the potential of air taxis. This faith is also apparently shared by Chinese carmaker Geely, which is currently the biggest investor in Volocopter and Daimler's largest shareholder. Geely and Volocopter want to set up a joint venture to introduce aerial mobility in metropolitan areas “onto the important Chinese market.”

Aerial relief for global megacities

The flying taxis are first and foremost set to be deployed over China’s megacities, which are plagued by traffic jams and smog, but also in India and South America. It’s here that aviation expert Stefan Levedag also sees the greatest need. "In Chinese megacities, there’s currently no way to get quickly from A to B. In big cities such as Sao Paulo, in addition to the time problem, there’s also a considerable risk of crime, which customers with deep pockets are of course keen to avoid,” says the head of the Institute for Flight Systems Technology at the German Aerospace Center (DLR) in Braunschweig.

Volocopter aims to be ready for market launch within the next three to five years. In ten years, it is anticipated that as many as 100,000 passengers per day will fly distances of up to 35 kilometres across giant cities at a cruising speed of 110 kilometres per hour. By way of comparison, public transport in Berlin carried an average of around three million passengers a day in 2018. Nor indeed is Volocopter seeking to replace earth-bound traffic: it aims instead to relieve some of the traffic burden on busy routes – for example, by ferrying people to out-of-town airports.

© Fraport AGSwitching from the aircraft to the flying taxi – the future?

According to the manufacturer, there’s no risk of aerial traffic jams caused by flying taxis. In a simulation, an air taxi was flown every twelve seconds on eight routes over New York at 70 kilometres per hour and at altitudes of between 100 and 350 meters. The aim is for the Volocopters to look hardly bigger than high-flying birds when seen from the ground.

Passengers will board and disembark at what will be known as VoloPorts, which the start-up wants to build on roofs, train stations or car parks. It’s also here that the batteries of the electrical aircraft will be automatically replaced and charged. Volocopter wants to offer a flight at double the fare for a taxi right from the start. “Once the system is fully operational, flying to a meeting won’t be much more expensive than taking a cab – and it’ll be faster to boot,” promises Alexander Zosel, co-founder of Volocopter.

More harmful to the environment than a car?

Experts have serious doubts as to whether the flying taxis will actually help the environment. A study by the University of Michigan found that they would consume less energy than an electric car or a conventional motor car carrying an average of 1.5 people only over distances of 100 kilometres or more and with three passengers on board. On routes of less than 35 kilometres, they would even need more energy, thereby producing more greenhouse gases than cars with internal combustion engines. And these are precisely the distances over which the air taxis will mainly fly in cities in the future.

“From an energy-use point of view, taking off vertically is the worst possible way of flying.”

But even if the aircraft were operated exclusively with green electricity, the technical problems are far from being solved, says Stefan Levedag of DLR. The biggest hurdle is precisely what automatically qualifies flying taxis for use in big cities: the combination of vertical take-off and electric drive. “From an energy-use point of view, taking off vertically is the worst possible way of flying,” the aviation expert says. Vertical-take-off aircraft require significantly more thrust at lift-off, and every kilo weighs more than it does in an aircraft which exploits the lift offered by its wings. Which is why even conventional helicopters can only fly much shorter distances and carry considerably fewer passengers than their fixed-wing counterparts. A problem that is further aggravated by electric propulsion. After all, because the energy density of today's lithium-ion batteries is 40 times lower than that of kerosene, you don’t get nearly as far with the same weight of fuel.

Is the range good enough?

According to Levedag, even the modest range of 35 kilometres that Volocopter proposes to offer would in practice be possible only in ideal conditions, “If you’re up against a headwind, the range drops dramatically,” the expert says. Moreover, the aircraft can’t make full use of their battery capacity. For safety reasons, they have to factor in energy reserves to allow them to fly to an alternative landing site in an emergency. It’s for this reason that management consultancy Roland Berger is convinced that it will take advances in battery technology and autonomous systems to give air taxis the decisive boost they need in the next five to ten years.

It also needs to be remembered that aircraft flying autonomously will save the weight of the pilot, which currently suppresses the range. However, according to Levedag, this will barely put a dent in the costs. After all, the systems need to perform the same flight tasks as a human pilot, reacting quickly to the instructions of the air traffic control system to avoid hazards presented by the weather and other aircraft. Although this is generally easier to do in the air than on the road, it’s still a major challenge both financially and technologically. “And, in terms of the regulations, we're still a long way away from that,” Levedag says.

A question of approval

Even manned air taxis will still have to overcome various legal hurdles before they are permitted to take to the skies. There is a need to clarify the regulatory issues presented by aviation over cities. After all, accidents would have particularly lethal consequences in such environments. What’s more, the city’s inhabitants are unlikely to take kindly to the additional noise. Although their electric propulsion and smaller rotors mean that the eVTOLs don’t make the same deafening noise as conventional helicopters, it’s fair to say that they aren’t completely silent in flight. Aviation parts supplier FACC doesn’t consider noise pollution to be a major problem. The noise made by the air taxis which are being developed in partnership with the Chinese company Ehang would be somewhere between that of a car and a lorry – and drones are likely to get even quieter in the future.

As the first “building block for the safe operation of VTOL aircraft”, the European Aviation Safety Authority (EASA) issued regulations in July 2019 for the development and construction of the new aircraft. Volocopter has developed its new VoloCity model in line with the EASA guidelines and is now awaiting certification. According to Airbus, European regulations allowing the commercial use of these aircraft will not be in place for at least another five years. At the same time, traffic management systems must be set up to ensure that drones can operate safely. To this end, Uber is working with NASA, which is developing suitable systems.

© Nikolay Kazakov for Volocopter / SkyportsThe so called VoloPorts serve as stations where passengers get on and off the flying taxis of start-up Volocopter.

For Stefan Levedag, whether air taxis will actually relieve urban traffic congestion is not least a question of cost. And the aviation expert believes that, at least initially, passengers will have to pay a fare more akin to that incurred by using a helicopter than a taxi. For this reason alone, it’s unlikely that flying taxis will become big business in Europe. “Our cities are simply too small to achieve a significant time saving compared to standard air transport.” According to Levedag, the benefits of the new high-flying mobility options will be felt primarily in places like Singapore, Hong Kong and Sao Paulo.The dream of flying over traffic jams may become a reality - but only for the few.

You may also like

ABOUT

© DLR

Stefan Levedag is the head of the Institute for Flight Systems Technology at the German Aerospace Center (DLR) in Braunschweig.