06. May 2021

Biofuels were being touted as the liquid changeover to environmentally friendly transport at the turn of the millennium. In the meantime, plant-based fuels have lost much of their lustre with policymakers and also with the public. So where do things stand with the climate-friendliness of biofuels today? And what role could they play in the future to reduce the carbon footprint of agriculture and aviation?

Batteries, fuel cells and electricity-based e-fuels: the building blocks of the environmentally friendly mobility of tomorrow already seem to be preordained. About 15 years ago, things were completely different. At the time, biofuels were considered the non plus ultra for climate-friendly transport. In the mid-2000s, oil prices were soaring. Biodiesel and vegetable oil fuels were hardly taxed at all and were starting to show their true colours as a low-cost alternative. Pure biodiesel was on sale at many petrol stations. And yet, thanks to successive tax increases after 2007, the price advantage increasingly dwindled away. As of 2013, biofuels became subject to the full amount of energy tax. The market for pure fuels collapsed.

For motorists, plant-based fuels have nevertheless been part of everyday life for years – albeit sometimes unnoticed and always in small doses. Whenever you fill your car with diesel, seven percent of what goes into the tank is automatically biodiesel, whether you like it or not. In Germany, it is mainly produced from rapeseed oil. If you drive a petrol car, you can refuel with either E5 or E10, i.e. petrol which consists of five or up to ten percent bioethanol. Ethanol is nothing other than alcohol which is obtained by fermentation from starchy and sugary plants. In Germany, sugar beet, wheat and rye are mainly used for this purpose.

By adding biofuels to their blend, oil companies are complying with their legal obligation to improve the carbon balance of their fuels in line with the greenhouse gas reduction rate. Since 2020, ten percent of the energy used in transport has had to be derived from renewable sources. Most of this currently comes in the form of biofuels. The production of these renewable raw materials now also plays an important role in agriculture. In 2016, raw materials “for energy and material use” were grown on around 17 percent of the arable land in Bavaria.

Are biofuels better than their reputation?

But plant-based fuels are far from uncontroversial. Biofuels from oil or food crops such as maize, rapeseed or cereals in particular have been viewed in a critical light for years. The accusation levelled at them is that they occupy valuable land which might otherwise be used for food production, thus prioritising fuel over food, as well as promoting monocultures - and even their environmental soundness is questioned now and then. From the point of view of the industry associations, this is a sweeping and overly universal criticism. In any case, rapeseed, which is particularly in demand for biofuel production in Germany, can’t be planted in the same field every year. In addition to oil, it also supplies what is known as press cake – protein-rich livestock feed from regional production, which replaces soya imports from South America. Glycerol, another by-product, is also used in the production of biodiesel. This sugar alcohol is used in toothpaste, skin cream and tablets. In Germany, according to the Verband der Deutschen Biokraftstoffindustrie (the Association of the German Biofuel Industry), VDB, glycerol from biofuel has now almost completely replaced the glycerol which was previously derived from petroleum.

The climate-friendliness of biofuels is also documented and securitised. Indeed, biofuels sold in Germany have been shown to generate at least 60 percent less CO2 than their fossil-fuel relatives. The calculation of the climate balance of plant fuel takes into account the emissions generated by fertilisation, harvesting, transport and fuel production. If the biofuel were to be produced from residual and waste materials such as straw, wood shavings or used fats, emissions could be reduced by as much as 90 percent. After all, no plants need to be grown in this recycling of residues.

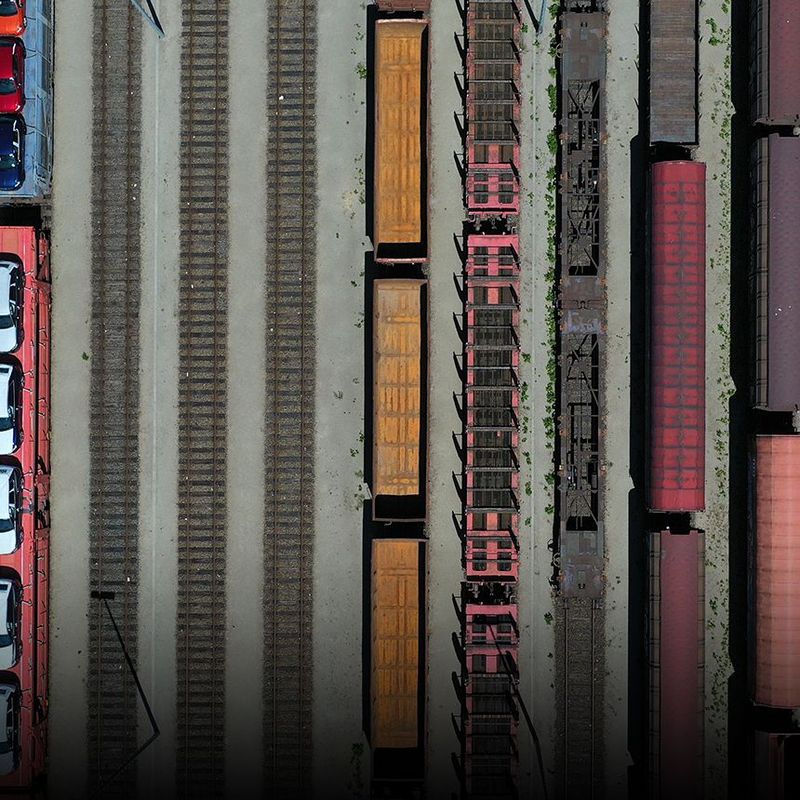

© iStockBiodiesel is mainly produced from rapeseed oil.

Generational conflict of biofuels

Such so-called second-generation biofuels are currently being produced only in small quantities. However, as far as policymakers at both EU and German government level are concerned, they are riding high in the popularity stakes. The German government is seeking to raise the greenhouse gas reduction rate, currently six percent, to 22 percent by 2030. The share of renewable energy in the electricity mix is about 28 percent. Biofuels from waste or straw are expected to account for at least 2.6 percent of it by then. The proportion of biofuel from food and feed plants is frozen at the current level of 4.4 percent.

Plants for which rainforest has been cleared or bogs drained have been strictly taboo as biofuel constituents in Germany since 2011. From a policy point of view, however, this cannot exclude the possibility that wheatfields in Europe will be converted to oil seed rape – and that the rain forests of Asia will be burned down to make way for urgently needed food production. The upper limit for agricultural biofuels and the use of a higher proportion of residues are intended to reduce this global problem.

Dispute over palm oil

The use of the particularly controversial palm oil will be gradually reduced as part of the legislative change and completely banned in Germany from 2026. With this schedule, Germany is clearly lagging behind other EU countries – such, at any rate, is the criticism of environmental associations such as the Transport & Environment NGO. In France, for example, palm oil-based fuel has not been considered a climate-friendly fuel since 2020, and in Austria it will no longer be counted as a biofuel from this July.

German biofuel associations fear above all else that the new law could lead to the elbowing out of biofuels from the market by other alternatives. The intention is for green hydrogen to double its share in the greenhouse gas reduction quota, while charging current for electric cars will account for up to three times its current share. This makes it much more attractive for oil companies to produce hydrogen and build charging stations than to add biofuels to gasoline and diesel, according to industry representatives. But even if policymakers were to largely set a course for e-mobility and hydrogen, the “advanced” biofuels from waste and residues would at least still be subsidised by a bonus. If more than the fixed minimum share were to flow out of German pumps, it would count twice over towards the quota.

Over the fields with plant-based fuel

But even straw, wood residues and other waste materials are not available in unlimited quantities. Biofuels are for this reason seen as the great white hope, especially in those areas where other alternatives are bumping up against their limits, for use, for example, in planes or farm tractors. It is true that manufacturers such as Fendt and John Deere have for several years been working on electric tractors which could be operated using solar power generated on barn roofs in an environmentally friendly and cost-effective manner. And yet, today's batteries are still too big, heavy and expensive to be used for a whole day’s farming without having to charge.

There is no doubting the fact that fuel cell tractors would be lighter and almost as fast to refuel as a diesel engine. However, both the technology and the fuel are currently still expensive. And unlike buses, for example, compact tractors do not offer enough space for large hydrogen tanks to be installed. As things stand today, H2 tractors would thus have to be refuelled every few hours. One solution would be to build hydrogen filling stations on farms – but such a thing currently costs a cool million euros.

Energy-rich liquid fuels seem to set to remain the measure of things for heavy agricultural machinery for the foreseeable future. Biofuels were being regarded as an environmentally friendly alternative to diesel in this sector back in the early 2000s. Biodiesel can now be used without any problems in different kinds of tractor, as can vegetable oil fuel, once the engine has been modified. But these have thus far failed to make significant inroads. It is for this reason that the Bavarian Ministry of Agriculture is looking to lead by example. 21 tractors and a wood harvesting machine which run on biodiesel or rapeseed oil fuel are already in use on state-owned Bavarian farms.

Compared to conventional diesel, it is anticipated that biodiesel will generate up to 80 percent fewer CO2 emissions as well as benefiting the environment in other ways. This is because it pollutes water and soil less than mineral-oil-based diesel, and fuel from rapeseed oil is easily biodegradable. From the point of view of the biofuel advocates, this is another important argument: after all, agricultural and forestry machinery is by its very nature used in environmentally sensitive areas.

© 2021 AGCO GmbHE-tractors already exist, fuel cell technology is still too expensive for agricultural equipment. Big hope: biofuels.

A matter of prices

However, the alternatives to diesel are not yet competitive. Farmers who fuel their vehicles with biofuels will be treated to a full refund of the energy tax levied on them. Even when this is taken into account, this fuel is still more expensive than tax-privileged agricultural diesel. But what might play into the hands of plant-based fuel in the future is the fact that the new CO2 levy will drive up the cost of petrol and diesel, whereas biofuels will be exempt. As diesel prices rise, biofuel could become more attractive to farmers. And as demand grows, it should also become easier for them to stock up on this environmentally friendly fuel. This is because biodiesel and rapeseed oil fuel are still available as pure fuels, albeit not as freely as they were ten years ago. Farmers currently have to order the fuel directly from producers or intermediaries at somewhat greater expense. Whether biofuel will one day manage to decisively overtake diesel on farms remains to be seen. The tax exemption for biofuels in agriculture officially expired on 31.12.2020. With the EU’s blessing, the German government has extended it until the end of 2021 – what will happen after that remains to be seen.

Will Biokerosene take off?

Things look more obviously promising when it comes to the use of biofuels at 10,000 metres above the Earth’s surface. As is the case with tractors, the use of batteries in large aircraft isn’t yet an option; hydrogen-powered aircraft are being developed but are not expected to arrive until the middle of the next decade. E-fuels from green electricity are being touted as the sustainable liquid fuel of the future – at least for heavy goods transport by water and in the air. However, some years are likely to elapse before they become available in larger quantities. Various airlines and aircraft manufacturers are convinced that biokerosene could be a way of making aviation more climate-friendly in the short term.

At the end of 2020, Lufthansa and DB Cargo sent a cargo plane fuelled with biokerosene from Frankfurt to Shanghai and back for the first time. Various other airlines and aircraft manufacturers have already gained some experience of what are known as Sustainable Aviation Fuels (SAF). Boeing, for example, has been offering its customers the option of adding biokerosene to the fuel blend on transfer flights since 2019. The aircraft manufacturer also wants to give its planes a technical upgrade. Under the current rules, a maximum of 50 percent of aviation fuel is permitted to come from alternative sources. By 2030, the group wants to make all its aircraft completely biokerosene compatible.

To date, however, sustainable kerosene has only been used very sparingly to refuel aircraft. According to EU figures, biokerosene or e-fuels account for just 0.05 percent of fuel consumption in Europe. This miniscule amount is not least a question of price. While biokerosene is cheaper than aviation fuel from green electricity, it is currently about four times as expensive as petroleum-based kerosene.

Refineries in the USA, the Netherlands and Singapore

Costs will fall as production increases. Moreover, indeed, refineries for biokerosene are being planned and also built worldwide: The British company Velocys is seeking to turn more than half a million tonnes of non-recyclable household and commercial waste into fuel every year from 2025 in a factory in the British isles. Manufacturer SkyNRG is planning a plant in the north of the Netherlands in which 100,000 tonnes per year will be produced from 2023. Dutch airline KLM will buy three quarters of the annual production. Fulcrum BioEnergy plans to start biokerosene production in the Nevada desert before the end of 2021. Every year, 175,000 tonnes of household waste will be converted into more than 40 million litres of aviation fuel. Manufacturer Neste is already producing 100,000 tonnes of alternative kerosene from waste oils and fats in Singapore. The Finnish company aims to increase its production capacity tenfold to one million tonnes per year by 2022.

What is already clear, however, is that biokerosene will never be as cheap to produce as its fossil fuel-based rival. Policymakers and the aviation sector are therefore increasingly calling for the EU to introduce a blending quota for biokerosene, as is already enshrined in law in Norway, for example. And there is a lot of evidence to suggest that the biokerosene blending quota will indeed be introduced in Europe. The European Commission intends to present a legislative initiative to boost the production and use of more environmentally friendly kerosene. Behind the scenes, there is speculation that the quota could be limited to flights in Europe – thus exempting long-haul flights. On the other hand, however, low-cost carriers such as Easyjet and Ryanair, whose short-haul flights would be particularly affected by the new rules, are mobilising. “Excluding long-haul flights would mean that the very part of our sector that most needs to be decarbonised would not be covered by this legislation at all,” say the airlines along with the Transport & Environment NGO.

Indeed, according to Eurocontrol, long-haul flights account for 51 percent of aviation sector emissions, but just six percent of flights. For the short-haul routes, the airlines explain, sustainable kerosene can in any case only be an interim step until such time as hydrogen or electricity-powered aircraft really take off in the 2030s. For long-haul flights, on the other hand, liquid fuels will still be indispensable even in the distant future.