20. January 2022

Lifts, turbines or entire factories can be digitally duplicated using sensor technology – for example, to remotely monitor whether they are working as they should. The concept whereby real things or processes are mapped digitally is known as the “Digital Twin”. Munich has taken this principle to a whole new level by creating a digital double of its entire urban space. In this interview, project manager Markus Mohl explains what the “Munich Digital Twin” is all about and how it might for instance help improve air quality and mobility in the city.

#explore: Mr Mohl, exactly what are we looking at with the Munich Digital Twin?

The digital twin is a dynamic and interactive 3-D model of the city and a collaborative urban data platform which is supplied with a wide array of data, from the city’s basic geographical data through to real-time data from sources such as traffic flow information and air pollution measurements. In the future, the digital twin will allow us to run through proposed changes in realistic simulations. This will allow experts to make better decisions based on more solid information, and local residents will also be able to get more fully involved in these decisions. Building a digital twin like this is, of course, a big challenge; after all, it’s a new and open-ended task, and other towns and cities haven’t yet created a digital twin of their own that we can simply adopt. Singapore has taken some big strides in this area – but there, of course, they have a completely different attitude to data protection which isn’t compatible with our European standards.

How did the idea for the digital twin come about?

It was first sparked off by the “Clean Air” subsidy programme introduced by the Ministry of Transport. This programme is supporting the digitalisation of municipal transport systems with the aim of reducing urban air pollution. We saw this as an opportunity to strike out on new paths in Munich. The first stage of the digital twin is accordingly focused on transport, mobility and improving air quality. Parallels can be drawn with an official city map – if you use the terminology of Industry 4.0, the analogue city map would be version 1.0 and the digital twin version 4.0. The latter includes much more data, which is also more up to date – especially with logical information about the city. In other words, we don’t just map the streetscape by sorting the urban space into footpaths, cycle paths, green spaces, car parks and roads; we go further by also recording the traffic rules that apply in those places. For example, how many lanes does a road have, and what speed limit is in effect on it?

© Digitaler Zwilling MünchenSafely embedded cycle lanes, a tram line, more trees (right picture): A visualisation of the plans for Boschetsrieder Straße in Munich.

„We can use the digital twin to play through scenarios to show what might happen if we made different changes. This will allow urban planning experts to identify the most effective measures more easily.“

And how can you use these data to improve mobility and air quality in Munich?

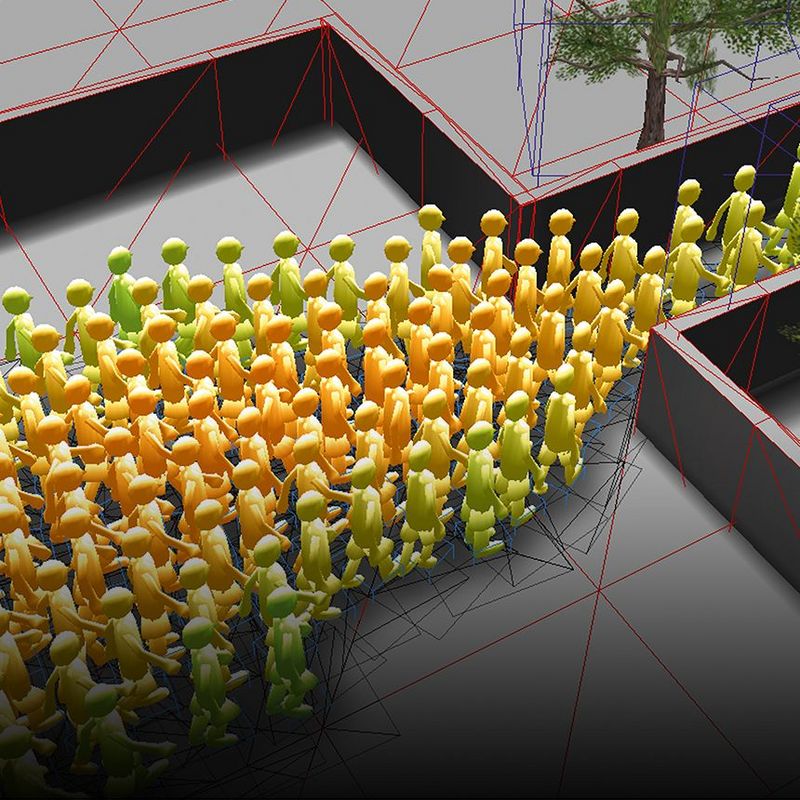

We can use the digital twin to play through scenarios to show what might happen if we made different changes, For example, how the traffic patterns would change and, with them, the air quality and the experience of local residents if we were to change the traffic light phases or replace car lanes with cycle lanes. This will allow urban planning experts to identify the most effective measures more easily, and we will at the same time be able to communicate the impact of the proposed changes more effectively to local residents. We’ll also be able use virtual or augmented reality to show such changes more clearly and make them into a hands-on experience. We started with this back in 2018 when we used augmented reality to visualise future building projects in the Freiham district. This enabled the residents to get a direct impression of how the proposed buildings would blend in with the urban landscape. With the support of the digital twin, we can and want to take these interactive routes more often in the future.

© Digitaler Zwilling MünchenSee what's coming: The upcoming construction measures in the Freiham district were illustrated using augmented reality.

What other applications might there be for the digital twin?

Not least due to global warming, heat in cities is becoming a growing issue – with consequences for the health of the people who live in them. Urban vegetation, for example trees, bushes and green spaces, are already included in the digital city map. This means that we can simulate the most efficient ways of cooling down heat islands: do we need to plant twenty new trees on a street, or would five be enough, and could we plant the remaining fifteen somewhere else? We can also use the digital twin to analyse and drive the expansion of the charging infrastructure for electric cars. We can see where charging stations have been installed and how they get used in the course of a day, a week or a year. Heat maps allow us to visualise where they’re particularly heavily used and where there’s less activity. In this way we can tell where the need is greatest. We can also give users recommendations in real time as to where they will find free charging stations.

Which other data sources do you want to use in the future and how will you guarantee that privacy is respected?

For those of us who work in the city administration, data protection is of course always the top priority. As a public administration we get given a certain amount of benefit of the doubt, which is something we want and need to repay. For instance, bike sharing data are always of interest and, from a technical point of view, it’s no problem to gather them – but privacy laws dictate that we can only do so with the consent of the users. And if they withhold that consent, then of course we don’t do it. The sensors on modern cars, which record a great deal of information in the urban environment, are another interesting data source. As these are mass data which can’t be used to trace an individual person, they’re less problematic in privacy terms.

Can such data simply be fed into the digital twin?

As we speak, we’re actually considering developing a standard for these data. But the question then arises as to whether the carmakers would be able to implement it. At the same time, it’s obvious that we can’t rely on the data provided by individual manufacturers. Data sovereignty is a fundamental value for us in the city administration. You can of course also use Google Maps for certain aspects of the digital twin. But if we want to preserve the sovereignty of our actions, we can’t allow our processes to become dependent on particular manufacturers or data formats. It goes without saying that, when it comes to actual projects, we also work with the business community. But you need to create a framework in the basic architecture of the digital twin that will guarantee this data sovereignty. This is one of the reasons why we set so much store by open standards and interfaces. And why we launch flights over the city and drive on its roads ourselves for our 3-D city model.

Will this approach also make it easier for cities to exchange digital information?

Absolutely. Cities are, after all, now confronted with very similar challenges. A digital twin of a city can help it master these challenges more effectively. If every town or city were to develop its own digital map from scratch, this would be neither economically viable nor efficient, and many local authorities simply wouldn’t be able to afford it. Which is why we’re placing so much faith in established standards and open-source software, because these will help us develop solutions which other cities can then adapt for their own use. We’ve teamed up with Hamburg and Leipzig to pursue this approach in the “Connected Urban Twins” project, which is being funded by the Ministry of the Interior.

In other words, you’re creating a blueprint for the digital twins of other cities, right?

Exactly. In specific terms, the “Connected Urban Twins” project is about using urban twins to come up with innovative approaches to integrated urban development. The idea is also to develop new formats to encourage the participation of local residents. Getting three cities to work closely together is, of course, a major challenge. That’s why we’re placing so much emphasis on dialogue, knowledge transfer and the replicability of the technical solutions that we’ve been talking about. And we hope this project will generate a signal effect at the European level.

In what other ways do you see the Munich digital twin developing in the next few years?

We see the digital twin as a community project. The more data we get from the different departments of the city and the more the twin gets used by different specialists, the better and more profitable it’ll become. We’re working on establishing the 3-D city model as an important database with ever larger amounts of information. And we’re developing efficient methods to update these data at ever shorter intervals. After all, that will be fundamental to our ability to create meaningful simulations. We also want to tap into and integrate other data sources. The idea is for Munich to be carbon-neutral by 2035 – with the digital twin we’ll be helping our urban community to achieve this goal.

About Markus Mohl:

© Privat

Markus Mohl is a geospatial expert who works in the GeoData Service of the city of Munich, where he is the director of the Munich Digital Twin Competence Centre.