21 March 2019

Demographic changes are being felt more acutely in nursing care than in almost any other area. While the number of people in need of care is growing, older nurses in particular are often taking early retirement due to the high levels of stress involved in its provision. One idea for the future is to use electronic nursing assistants to counteract the acute shortage of trained staff.

Deep down in bowels of the Cologne University hospital, they are already bustling around. 91 robots are whirring through the 6 km-long system of underground corridors and hallways that connect the clinic buildings. The flat robotic carts were originally developed for industrial logistics. In the Cologne University hospital, they are ferrying about wheeled containers which contain such items as food or clothes for the patients. On anything up to 3,000 daily journeys, which are controlled by a central computer system, they follow fixed routes which they navigate using sensors. In the Jena University hospital or Krankenhaus Nord in Vienna battery-operated logistics robots are also carrying food and materials from A to B - unnoticed by patients or visitors. However, visitors to, and potentially also the residents of, care homes for the elderly might soon be in daily contact with robots. This is for very pragmatic reasons.

Using robots in the fight against the crisis in nursing care

According to calculations of the German government, in 2017 there was a shortfall of some 35,000 nurses in German hospitals and old people’s homes. The situation in care for the elderly is especially dramatic: Only 21 unemployed professionals were appointed to fill a total of 100 vacancies. This is a problem that is being further aggravated by demographic change: By 2025, the Federal Statistical Office predicts that there will be a shortfall of 200,000 nurses. In a study, the Bertelsmann Stiftung raises the possibility of 430,000 vacancies by 2030. The idea for the future is to use electronic nursing assistants to help counteract the shortage of trained staff. In Japan, where birth rates are particularly low compared with other industrialised countries and the number of retirees is higher than average, experiments with robots have been conducted in the nursing care sector for years. The German Ministry for Education and Research is also set on exploring the potential for robots in nursing care and is subsidising pilot projects in this area to the tune of 20 million Euros.

For example, the ministry is helping to finance a project entitled “Anwendungsnahe Robotik in der Altenpflege“ (ARiA) (“Applied robotics in care for the elderly”) that is being run by the universities of Kiel and Siegen. Among other things, the researchers have been taking a lady robot called Emma to visit a residential group of dementia patients. She does memory training exercises with the residents, plays Memory, asks quiz questions, dances or reads aloud to them. Emma’s real name is actually “Pepper”, and she was developed by a subsidiary of Japanese technology company SOFTBANK to recognise human speech, gestures and facial expressions. Hotel chains are using her on reception, and in Munich Airport, she shows passengers the way to the terminal; care researchers, too, have now discovered this wide-eyed lady robot, who costs some 17,000 Euros, for themselves. As Volker Wulf, Professor of Business Information Technology at the University of Siegen, explains, the researchers from Kiel and Siegen want to find out how such robot a can “improve the quality of life” of both senior citizens “and caregivers”. They are testing the responses of residents and nursing staff to Pepper and working with the latter to develop applications for the robots which can be used to calm elderly residents down, get them to be more active or stimulate their memory. This is especially important for dementia patients. The idea is not, of course, to replace human carers but instead to relieve them of certain tasks to give them more time to actually look after the senior citizens in their charge.

Relieving, not replacing

As Birgit Graf from the Fraunhofer Institute for Manufacturing Engineering and Automation, IPA, emphasises, most of the social activities which make up a large part of care work will remain the preserve of human carers. “Even in the long term, robots are not going to master interpersonal communication or interaction sufficiently well to allow them to replace people,” says the director of the Household and Assistance Robotics group at the IPA. The skill set of the electronic assistants does not include the ability to listen, empathise and tacitly understand patient needs. How robots may be able to take the burden off caregivers, saving them time and making the job less physically onerous, is the subject of research being carried out by Graf and her colleagues in Stuttgart.

“Even in the long term, robots are not going to master interpersonal communication or interaction sufficiently well to allow them to replace people.”

So that staff will in future have to spend less time running around and documenting materials used, the team has developed an “intelligent nursing cart” in the context of the “SeRoDi” project with partners including the manufacturer MLR. The caregiver summons the cart to the desired place by smart phone, and it then navigates independently to the destination, even taking the lift if need be. Using a 3-D sensor, the nursing cart then identifies the material it dispenses. If time is tight or its battery is starting to run low, given appropriate clearance by the staff it then takes itself back to the store room or charging station.

Intelligent nursing carts

The nursing cart was tested over several weeks in two old people's homes and at the University Hospital in Mannheim. Whereas in the homes it was responsible for ferrying laundry around, in the hospital it supplied the nurses with bandages. These are taken from modular baskets, which can be filled up by the hospital’s logistics staff and quickly and easily swapped by the nurses on the wards. The next stage of the plan is to automate basket switching to save the staff yet more time. Even at this early stage, however, as Graf relates, the perception among the nurses has been that the nursing cart has relieved them of some of their burden.

© Fraunhofer IPAThe intelligent nursing cart arrives in response to an order delivered by smart phone, bearing whatever is needed.

Like the transportation robots in the university hospital in Cologne, the nursing cart follows fixed routes. If it encounters an obstacle, it simply trundles around it before getting back onto its programmed track. To ensure that the cart neither lags behind the brisk pace of day-to-day care nor scares patients by scooting along too fast, it is capable of adapting its speed dynamically to the situation it finds itself in. If its sensors detect an obstacle, it reduces its speed well ahead of time. To further optimise the robot’s operation, Graf and her colleagues are working on a sensor which can distinguish between people and other obstacles. “If, for instance, there’s a meals trolley in the corridor, it can pass by faster than it would if a person were standing there,” the IPA engineer explains.

The robot serves drinks

As well as the intelligent nursing cart, the residents of the Waldhof home for the elderly in Mannheim have also become acquainted with the robotic service assistant. When they were sitting in the lounge, the service assistant would trundle by and speak to them to offer them a drink that they could then select via a touch screen. It had previously been loaded up with drinks by the nursing staff and sent out on its rounds. It would then use a map of the surroundings to navigate the best route to the residents. The senior citizens had absolutely no reservations about it, Graf relates. The robotic assistant was also well received by the nurses. “The feedback was very good; after all, the staff don’t always have the time to be there in person to make sure that the residents are drinking enough,” the engineer says. A further development stage might see the robot being linked with documentation software so that staff will always know which drinks were dispensed to whom. Greater individualisation of the system is also planned. Linking the robot to the patient database would also allow the service assistant to respond specifically to any intolerances on the part of individual patients.

Supporting nursing staff

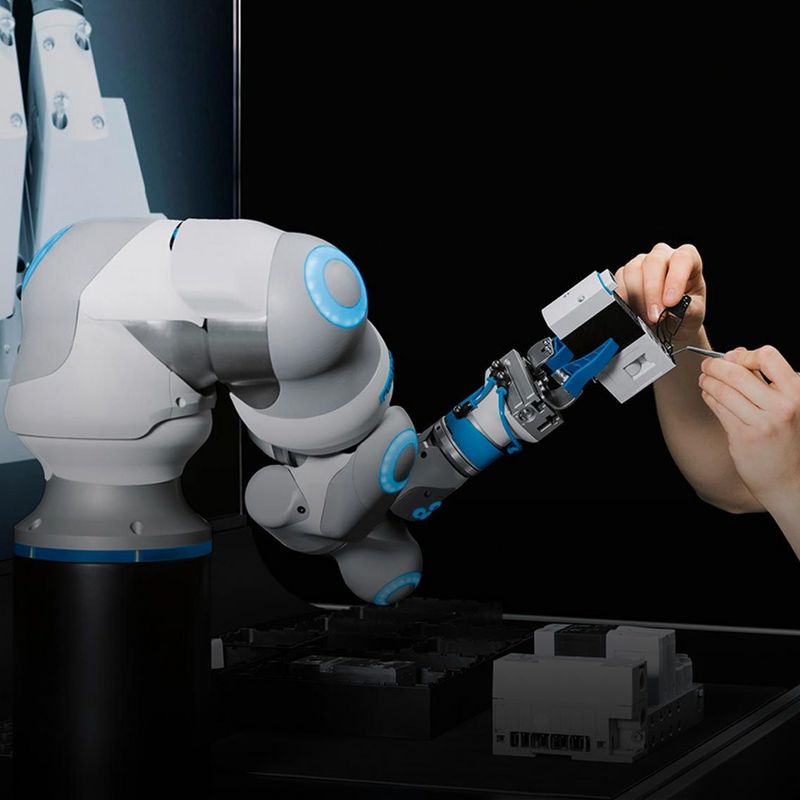

The intention is also for robots to ease the physical strains of the nursing profession. According to a survey conducted by Germany’s Federal Institute for Occupational Safety and Health, nurses have to carry more material about than construction workers. “In industry, for instance in installation work, there are all sorts of aids to reduce physical strain to a minimum. Here we see an urgent need to equip nurses with the same kind of aids,” Graf explains. For example, robots could lend a hand when it comes to lifting patients or changing their bedding, also indirectly helping to assure that nurses don’t quit the profession early because of the sheer physical strain. “If we manage to keep people who’ve been working in this job for many years and want to carry on doing so, then we’ll have achieved a lot,” says Birgit Graf. The engineer and her team have for instance developed a multi-functional lifter by the name of “Elevon” that finds its own way to where it is required and actively helps the nurse with patient registration. There are still some technical challenges to overcome before such systems will be ready for series production, the expert says. As the robots need to be very strong, any malfunction might potentially also entail greater risk to the patients. “If we’re going to be able to make these systems safe, new technical solutions will have to be developed which aren’t yet available on the market, Graf notes.

© Fraunhofer IPAIn the Waldhof care home for the elderly in Mannheim, the service assistant relieves the caregivers of a task that is crucially important for elderly people: their fluid intake.

In principle, exoskeletons also offer a great deal of potential when it comes to helping nurses lift patients. However, their development is faced with technical challenges similar to those associated with autonomous carrying robots. “If they are to be integrated into everyday nursing work, it needs to be possible to put them on and take them off quickly, and they should be as inconspicuous as possible,” Graf explains. After all, no-one wants to the elderly residents to get a shock when the robo-nurse comes through the door.

Start of production is still some way away

To date, robots for use in nursing have barely made it beyond the prototype phase anywhere in the world. According to Birgit Graf, however, this could change in the next few years, first of all with transport and assistance robots. “Technically speaking, these systems are already very well developed,” the engineer says. And the use of these expensive devices could also pay off economically: “Assuming that tasks are selected so as to ensure that the robot is consistently busy and doesn’t spend half the day standing unused in a corner,” Graf explains. And yet, other opportunities will have to present themselves for clinics and care homes to finance such major investments. These are currently very limited. “Some manufacturers are already thinking here about leasing models. But from my point of view, the state will have to come up with appropriate funding models,” recommends the robotics expert.

The German public is in any case pretty open-minded when it comes to the use of robots in nursing: 26 percent of respondents to a representative survey carried out by the “Technische Krankenkasse” health insurance provider assume that, in ten years, every person in need of care will be assisted by a robot. Nearly 60 percent would be happy to be helped by a robot even now.

ABOUT

© Fraunhofer IPA

Dr. Birgit Graf is director of the Household and Assistance robotics group at the Fraunhofer Institute for Manufacturing Engineering and Automation, IPA, in Stuttgart.