Future of rail transport

Magnetised race

How China and Japan are seeking to use maglev trains to compete with air travel.

Future of rail transport

How China and Japan are seeking to use maglev trains to compete with air travel.

16. December 2021

China has the most extensive rail network for high-speed trains in the world, whereas Japan holds the record for the most punctual. Both nations are now planning to significantly increase the speed of their trains – using rapid magnetic levitation trains to close the gap with air travel.

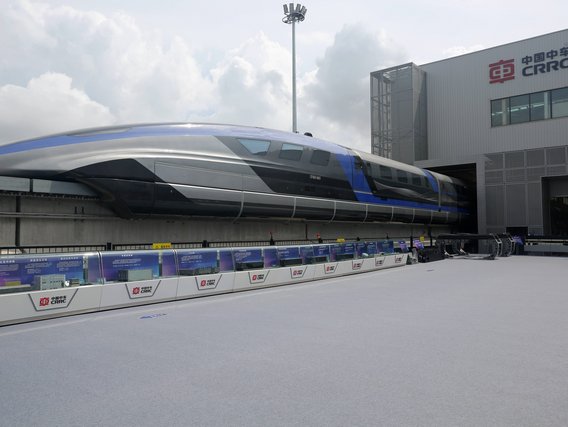

The rail network for high-speed trains in China is already some 38,000 kilometres in size. The second largest network in the world covers much of Spain but is barely one tenth as big. Running at a speed of around 350 kilometres per hour, China’s Fuxing is currently the world’s fastest train in regular operation – but it is likely to face competition in its homeland in the future. In July, the first high-speed maglev train rolled off the assembly line in the city of Qingdao: It is expected to reach speeds of 600 kilometres per hour, making it the “fastest land vehicle in the world”, according to state-owned Chinese company CRRC. The train is now set to be tested over a period of several years, with suitable tracks for maglev trains to be built at the same time. According to the Chinese government, Shanghai, Chengdu and other major cities and provinces of the country are planning fast connections by maglev train.

On routes of up to 1,500 kilometres, this system, which is being developed entirely in China, might even prove faster than flying. While it takes about two hours to get from Beijing to Shanghai by air, a passenger on a maglev train could expect to reach their destination in just 2.5 hours, and that measured from city centre to city centre. The first trains could be in operation in five to ten years. In technological terms, China wants to catch up with its neighbour Japan, where work is also being done on maglev trains.

Japan launched the world’s first high-speed trains in 1964. The Shinkansen are now considered the most punctual and safest express trains on the globe. This is ensured by a completely separate and almost entirely fenced-in rail network, which the trains – unlike the ICEs in Germany – do not have to share with regional trains and freight traffic. Since the 1970s, Japanese engineers have also been working on their own maglev train system. In 2015, the maglev became the first train on earth to break the 600 km/h mark. With its 15-metre-long nose, the Maglev L0 is reminiscent of a pike on rails. This is intended to ensure optimal aerodynamics and also a quieter ride by preventing the loud bang that high-speed trains generate when they race into narrow tunnels at full speed.

Technologically speaking, the Japanese maglevs are already much further ahead and closer to series production than their Chinese counterparts, says Hans Vallée, railway expert at TÜV NORD. “After all, Japan has had test tracks for these vehicles for decades.”

The fact that the two nations are taking different technical paths has geological reasons, among others, according to Vallée. China has placed its faith in the Transrapid principle. The track acts simultaneously as a propulsion system: the motor uses what is known as a long stator, which “unrolls” along the length of the entire guideway, which consists of a single rail enclosed by the underside of the vehicle. In the Japanese system, the drive with its short stator is shifted into the vehicle, and the train sits in a U-shaped trench. Due to the magnet technology used, the Japanese suspension railways have a larger air gap between the track and the vehicle – thereby offering more of a cushion in the event of earthquakes, which are not uncommon on the island state.

The production version of the Japanese maglev is expected to reach a top speed of 620 and cruising speeds of 500 kilometres per hour. The 286-kilometre maiden route from Tokyo to Nagoya would then be covered by the new train in 40 minutes. Today, the Shinkansen takes twice as long. The second stage of the plan is to extend the route of the maglev train to Osaka. The connection between the three economic centres is now the busiest route in Japan and runs at full capacity with some 143 million passengers per year. The fast maglev train is intended to remedy this situation – and its passengers will be whisked largely through tunnels on an almost completely straight route through the Japanese Alps.

„A maglev train can travel at a significantly higher speed using the same energy as a conventional high-speed train, in part due to the lower friction losses.“

Hans Vallée, expert in and appraiser of functional safety at TÜV NORD with a focus on railways

The head-to-head race to create the fastest train on the planet is partly about prestige, but above all about export markets. The populations of numerous emerging economies are growing – and with them the need for efficient transport networks. Experts estimate the export potential of new train technologies at around 1.6 trillion euros. And since the maglev trains require relatively small amounts of electricity, they are also considered promising from a climate protection point of view. “A maglev train can travel at a significantly higher speed using the same energy as a conventional high-speed train, in part due to the lower friction losses,” explains train expert Hans Vallée.

Whether the maglev trains will actually become an export hit is far from clear. After all, to recoup the high additional costs compared to rail-bound trains would require colossal demand. And the maiden Japanese route from Tokyo to Osaka, with its concentration of megacities, is regarded globally as an absolute exception to the rule. “High-speed maglev trains require their own expensive infrastructure. Without subsidies, these systems wouldn’t be able to compete with air travel under current conditions, for example,” says Vallée. Japanese manufacturer JR Central has high hopes for the US market – and is bidding to construct a maglev line between Washington DC and New York. In return for the opportunity to establish its system internationally, it would forego any claim to royalties.

What other applications might there be for the digital twin?

Not least due to global warming, heat in cities is becoming a growing issue – with consequences for the health of the people who live in them. Urban vegetation, for example trees, bushes and green spaces, are already included in the digital city map. This means that we can simulate the most efficient ways of cooling down heat islands: do we need to plant twenty new trees on a street, or would five be enough, and could we plant the remaining fifteen somewhere else? We can also use the digital twin to analyse and drive the expansion of the charging infrastructure for electric cars. We can see where charging stations have been installed and how they get used in the course of a day, a week or a year. Heat maps allow us to visualise where they’re particularly heavily used and where there’s less activity. In this way we can tell where the need is greatest. We can also give users recommendations in real time as to where they will find free charging stations.

Which other data sources do you want to use in the future and how will you guarantee that privacy is respected?

For those of us who work in the city administration, data protection is of course always the top priority. As a public administration we get given a certain amount of benefit of the doubt, which is something we want and need to repay. For instance, bike sharing data are always of interest and, from a technical point of view, it’s no problem to gather them – but privacy laws dictate that we can only do so with the consent of the users. And if they withhold that consent, then of course we don’t do it. The sensors on modern cars, which record a great deal of information in the urban environment, are another interesting data source. As these are mass data which can’t be used to trace an individual person, they’re less problematic in privacy terms.

Can such data simply be fed into the digital twin?

As we speak, we’re actually considering developing a standard for these data. But the question then arises as to whether the carmakers would be able to implement it. At the same time, it’s obvious that we can’t rely on the data provided by individual manufacturers. Data sovereignty is a fundamental value for us in the city administration. You can of course also use Google Maps for certain aspects of the digital twin. But if we want to preserve the sovereignty of our actions, we can’t allow our processes to become dependent on particular manufacturers or data formats. It goes without saying that, when it comes to actual projects, we also work with the business community. But you need to create a framework in the basic architecture of the digital twin that will guarantee this data sovereignty. This is one of the reasons why we set so much store by open standards and interfaces. And why we launch flights over the city and drive on its roads ourselves for our 3-D city model.

Will this approach also make it easier for cities to exchange digital information?

Absolutely. Cities are, after all, now confronted with very similar challenges. A digital twin of a city can help it master these challenges more effectively. If every town or city were to develop its own digital map from scratch, this would be neither economically viable nor efficient, and many local authorities simply wouldn’t be able to afford it. Which is why we’re placing so much faith in established standards and open-source software, because these will help us develop solutions which other cities can then adapt for their own use. We’ve teamed up with Hamburg and Leipzig to pursue this approach in the “Connected Urban Twins” project, which is being funded by the Ministry of the Interior.

In other words, you’re creating a blueprint for the digital twins of other cities, right?

Exactly. In specific terms, the “Connected Urban Twins” project is about using urban twins to come up with innovative approaches to integrated urban development. The idea is also to develop new formats to encourage the participation of local residents. Getting three cities to work closely together is, of course, a major challenge. That’s why we’re placing so much emphasis on dialogue, knowledge transfer and the replicability of the technical solutions that we’ve been talking about. And we hope this project will generate a signal effect at the European level.

In what other ways do you see the Munich digital twin developing in the next few years?

We see the digital twin as a community project. The more data we get from the different departments of the city and the more the twin gets used by different specialists, the better and more profitable it’ll become. We’re working on establishing the 3-D city model as an important database with ever larger amounts of information. And we’re developing efficient methods to update these data at ever shorter intervals. After all, that will be fundamental to our ability to create meaningful simulations. We also want to tap into and integrate other data sources. The idea is for Munich to be carbon-neutral by 2035 – with the digital twin we’ll be helping our urban community to achieve this goal.

This is an article from #explore. #explore is a digital journey of discovery into a world that is rapidly changing. Increasing connectivity, innovative technologies, and all-encompassing digitalization are creating new things and turning the familiar upside down. However, this also brings dangers and risks: #explore shows a safe path through the connected world.