24. June 2021

Deutsche Bahn aims to be carrying twice as many passengers and significantly more freight than today by 2030 – and that without adding a single metre of additional track. If all goes well, digitalisation, automation and artificial intelligence will send trains out into the network at shorter intervals and with improved punctuality, thereby advancing the cause of the transport transition. The Group wants to offer a foretaste of the automated future this autumn in Hamburg.

“Digital ist besser” (“Digital is better”) was the refrain of the band Tocotronic 26 years ago. This song title was meant ironically at the time – but it would be hard to overstate just how high corporate expectations now are of digitalisation. Deutsche Bahn is no exception. The Group anticipates nothing less than a revolution in the railway system, to be catalysed by its major “Digitale Schiene Deutschland” (“Digital Rail Germany”) project. Signal boxes and points will be operated digitally, and the control and safety technology for the trains will function via radio and sensors. And more and more processes could run automatically. Stopping just short of the trains themselves, whose drivers will continue to perform monitoring functions. The goal of the digital transformation of rail transport is to have more punctual and reliable trains that can carry considerably more people and goods on the same routes at shorter intervals. Without building any additional tracks.

Nine metres of new track

The expansion of the rail network in Germany is faltering in any case: in 2019, just nine kilometres were added. During the same period, new roads were built, and existing ones upgraded, adding 233 kilometres to the motorway and trunk road network. Associations from the railway industry have for this reason been calling for some time for significantly higher investments in the expansion of the railway infrastructure. One thing is clear, though: the construction of new lines is time-consuming and can often take 20 years or more to complete. In addition to demanding approval procedures, nature conservation regulations and the complaints of residents, experts assign the responsibility for this glacially slow process to the lack of specialist personnel in official bodies, construction companies and Deutsche Bahn itself. A shortcoming that can’t be remedied overnight. This explains why Deutsche Bahn is seeking to get the most out of the existing network by digitalising it nationwide. To do this, it must first grow out of the existing infrastructure, which is in places still decidedly analogue in character.

Points with IP addresses

Many of the 2,600 points in Germany are either mechanical or electromechanical. Some of them date back to the age of the Kaisers. There is no way a digital rail infrastructure could be built on this. This is why Deutsche Bahn wants to gradually take the analogue technology out of circulation and replace it with digital signal boxes. Instead of using a power cable as before, the control commands for signals and points will then be transmitted via fibre optic data cables.

The decisive advantage from Deutsche Bahn’s point of view is that the digital signal boxes will cover larger areas, so considerably fewer of them will be needed. 280 digital signal boxes should be sufficient to control all rail traffic on the 33,400-kilometre network in Germany. It will moreover be possible to detect and remedy the causes of faults and failures of points and signals more quickly by going digital. Last but not least, the digital signal boxes should be able to manage with much less expensive cabling. However, the new signal boxes will only unfold their full potential in conjunction with the European Train Control System (ETCS for short), which Deutsche Bahn is also seeking to introduce in parallel.

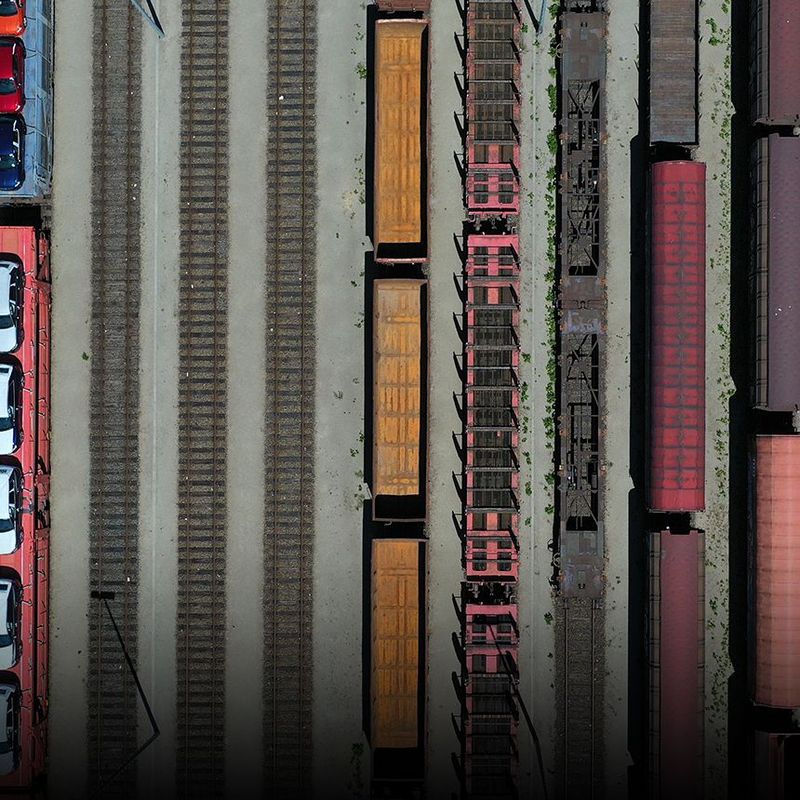

© Deutsche Bahn AG / Oliver LangStep by step, all of the railroad's 2,600 analog interlockings are becoming digital.

Safety system with radio and sensors

The ETCS was developed to facilitate cross-border rail traffic. This is currently still being held up by different national train control and safety systems. Above all, however, thanks to the technology, trains can run at shorter intervals on the same route. Until now, it has only been possible for one section of the line – called a block in railway jargon – to be used by one train at a time. In view of the braking distance, which can in some cases run into kilometres, sufficient distance to the train in front is otherwise not always guaranteed.

With ETCS, all trains are located via radio, sensors and transponders in the tracks – so-called Eurobalises – and their speed is recorded. The train receives its driving commands from the ETCS route control centre. This computer unit uses the transmitted data to calculate which section of the route is free and how fast the train in question can travel safely without risking a rear-end collision, thereby rendering block distances superfluous. The train drivers use on their on-board computers to see up to 30 kilometres of the route ahead of them, and the system warns them at an early stage if they need to slow down and, in case of doubt, automatically initiates braking. Deutsche Bahn hopes in this way to introduce 20 percent more trains onto the network– along with a corresponding number of new passengers. Even the approximately 160,000 signals in operation today will no longer be needed in the future and will in any case no longer be able to stop trains if they fail.

© picture alliance / dpa / Peter EndigThe European Train Control System ETCS is intended to coordinate rail traffic across borders.

Speeding things up with digitalisation?

There are currently only a handful of digital signal boxes in Germany. And, unlike in some neighbouring European countries or in China, ETCS is only in use on a few routes in Germany: for example, between Berlin and Dresden, Erfurt and Leipzig/Halle and on a section of the ICE parade route from Berlin to Munich. But this is set to change faster than was originally planned. Seven outdated signal boxes on regional lines in North Rhine-Westphalia, Rhineland-Palatinate, Thuringia and Bavaria are being converted ahead of time to digital technology. These “high-speed projects” are being financed by the German government's coronavirus economic stimulus package.

Highly automated through Hamburg

Deutsche Bahn wants to offer a foretaste of the future this October in Hamburg at the ITS Congress, the world's largest event for smart transport systems. Between the S-Bahn stations Berliner Tor and Bergedorf/Aumühle, highly automated trains will then run through the Hanseatic city for the first time. Four S-Bahn (urban train) railcars will be equipped with ETCS and the ATO system (Automatic Train Operation), and the 23-kilometre route will also be prepared accordingly. Starting, accelerating, braking and stopping will be controlled by the vehicles alone, which will also open the doors independently at the stops. There will still be a driver on board, however, who will be able to step in if a fault or some kind of irregularity should develop. The only fully automated section will be the S-Bahn turning point at Bergedorf station. Here, the driver will disembark with the passengers and wait until the automated train has repositioned itself for the journey to Berliner Tor. The train control information for fully automatic operation will be transmitted via a 5G mobile network, which Deutsche Bahn is testing for the first time for this purpose.

Thanks to this automation of operations, project manager Jan Schröder raises the prospect that the S-Bahn operating company will be able to reduce the interval between trains from the current three minutes to less than 90 seconds. Significantly more trains will run on the same route. If the project is successful, it could be rolled out throughout the Hamburg S-Bahn network. Deutsche Bahn is optimistic that many of the trains and lines used in local and long-distance traffic throughout Germany could follow in the next 15 to 20 years.

© Deutsche Bahn AG / Andreas VarnhornThe first highly automated commuter trains will be in service in Hamburg from autumn onwards.

“Digital Node Stuttgart”

The first large-scale test of automation is planned for Stuttgart. The main line of the local S-Bahn is chronically congested. As part of the construction of Stuttgart 21, the route network of the state capital must in any case be equipped with new control and safety technology. The aim, therefore, is for around 125 kilometres of long-distance, regional and S-Bahn lines to be equipped with ETCS, ATO and a digital signal box. By 2030, the entire network up to the S-Bahn terminuses should follow.

“We hope that we will be able to run 30 S-Bahn trains per hour instead of the current 24 along Stuttgart’s main line,” Kristian Weiland, head of the Group's Digitale Schiene Deutschland programme, told ZEIT Online. Automation can also minimise delays by accelerating trains to the permissible maximum speed and slowing them down again as soon as they are back on schedule. From 2030, the new TMS traffic control system will then further optimise train operations by collecting and evaluating data sent by the trains and the infrastructure. If, say, two trains are heading for a single-track section at the same time, the TMS will intervene, for example, by slowing one of them down at an early stage, thereby avoiding unnecessary stops and delays. Because the trains will have to stop and start less often, this more dynamic form of traffic management could also reduce wear and energy consumption. Throughout Germany, Deutsche Bahn hopes to save 1.6 million tonnes of CO2 per year through the measures taken by the Digitale Schiene alone. This would amount to three quarters of the volume emitted by domestic flights in 2017.